If Elvis Presley was the King of rock ‘n’ roll, Buddy Holly was its greatest ambassador. One made a generation of British boys fall in love with rock, the other showed them how to play it for themselves.

Holly’s songs, like ‘That’ll Be The Day’, ‘Oh Boy’ and ‘Peggy Sue’, are timeless classics, as fresh and innovative today as when he recorded them with his group the Crickets on the most basic equipment in the late 1950s.

Sixty-six years after his death, his continuing vast influence is celebrated in a limited-edition picture book titled Words Of Love containing tributes from major musical talents of every era from Paul McCartney, Keith Richards and Bruce Springsteen to Nile Rogers, U2’s The Edge and Yungblud.

If this sounds too much like a boys’ club, there are fond messages from Dolly Parton, Linda Ronstadt, Emmylou Harris and Joan Jett whom he also encouraged without ever knowing it.

As his biographer, I was asked to speak at the book’s recent launch-party to an audience including the Rolling Stones’ Ronnie Wood and Roger Daltrey of The Who. We were all equals that day in our love and mourning for Holly.

He was the first guitar hero with his flat-bodied, spear-headed Fender Stratocaster, the look somehow enhanced by his studious-looking horn-rimmed glasses as if he’d passed every exam in being cool. His hiccuping vocal style, which could fracture the word ‘well’ into eight separate syllables, has been mimicked countless times but never replicated

His death in a plane-crash, aged only 22, was rock ‘n’ roll’s first and worst tragedy, forever enshrined in Don McLean’s ‘American Pie’, as ‘the day the music died.’

Of course it did no such thing. Singer-songwriter and brilliant lead guitarist, Holly begat the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Who, the Hollies and almost every other major British band of the Swinging 60s. And every one of the thousands of bands who copied them, knowingly or not, had a bit of Buddy in them.

He was born Charles Hardin Holley to strict Baptist parents in the West Texas city of Lubbock in 1936. He took up the guitar as a small boy, proved a natural performer and was soon playing live with other juvenile partners on radio stations in the area.

Like everything else in Lubbock – and throughout the American South – music was subject to strict racial segregation with only designated ‘black’ stations providing blues, gospel and r&b. To Holley’s God-fearing parents, they were all forms of original sin which he could listen to only in secret, late at night on the radio of the family car.

In 1955, Elvis Presley – then still only a regional phenomenon, billed as ‘The Hillbilly Cat’ – played a gig at Lubbock’s Fair Park auditorium, fusing country and R&B with the latter’s overt sexuality. Between shows, unrecognised and rather lonely, he hung out with 19 year-old Holley and his friends, though doing nothing wilder than seeing a movie together.

In the stampede to find ‘new’ Elvises, Holley won a recording-contract with the Decca label in country music’s capital, Nashville, Tennessee. Decca’s contract misspelt his surname ‘Holly’ and he decided to keep it that way.

The material he took into the studio included a song he’d written with his best friend, drummer Jerry Allison, after seeing John Ford’s classic Western The Searchers. Its title borrowed a phrase John Wayne drawls throughout the film: ‘That’ll be the day.’

But the session was a disaster. Decca’s producer, Owen Bradley, had no idea what to do with the hiccups, swoops and sighs of Holly’s voice and hated ‘That’ll Be The Day’, dismissing it after 19 takes as ‘the worst song I ever heard.’

Then Holly heard tell of an independent producer named Norman Petty with a recording-studio in Clovis, just over the Texas-New Mexico state line, where young musicians were allowed to develop their material without the soulless clock-watching of big companies like Decca.

Petty agreed to re-record ‘That’ll Be The Day’ and transformed the lacklustre Decca version with blurry double-tracking and a major role for Holly’s ringing, back-somersaulting lead guitar.

Petty had contacts in the New York record business and, after a few rejections, placed ‘That’ll Be The Day’ with the Coral label, at that time best-known for middle-of-the road acts like Debbie Reynolds, Teresa Brewer and the Lawrence Welk Orchestra.

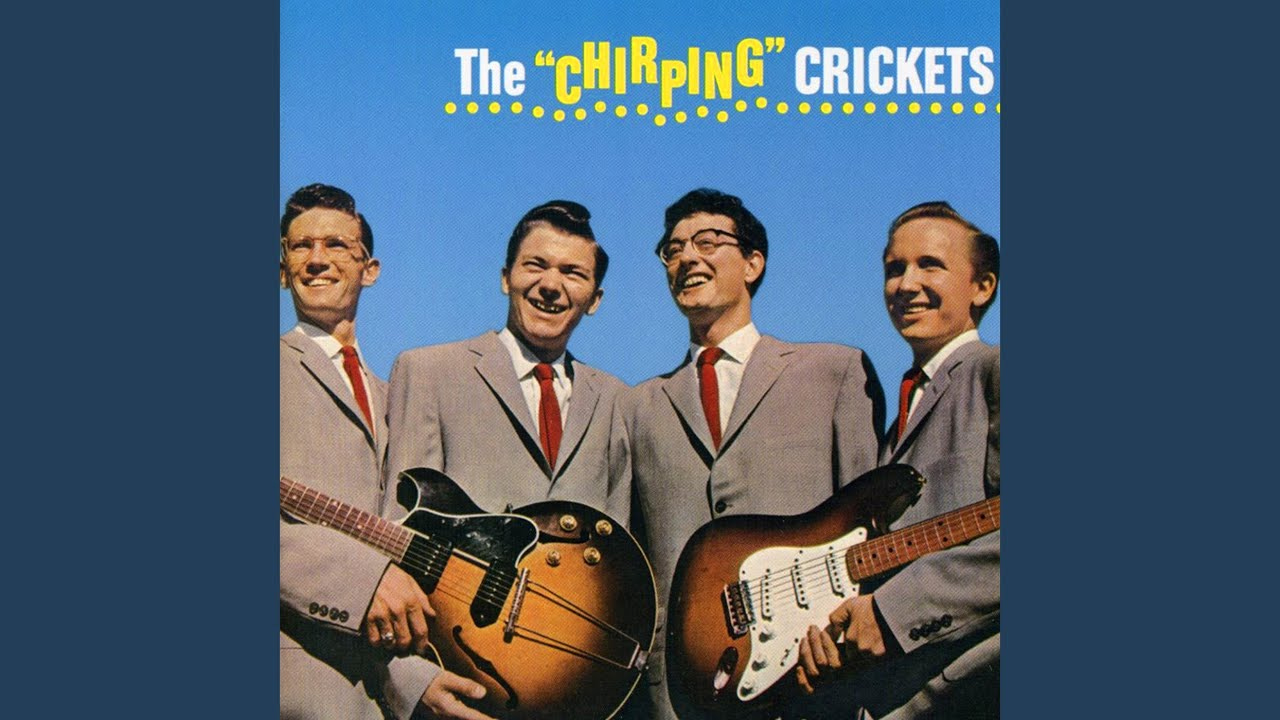

Coral’s acquisition were initially a quartet consisting of Holly, Jerry Allison on drums, Joe B. Mauldin on stand-up bass and on rhythm guitar Holly’s cousin Niki Sullivan who unbalanced the lineup by strongly resembling him, even down to the glasses.

Technically, Holly was still under contract to Decca and debarred from recording on Coral, so the group needed to hide his presence behind a collective name. They toyed with the idea of calling themselves the Beetles until one night a cricket, found its way into the studio and emitted a loud double chirp perfectly in sync’ with the end of the track they were working on, ‘I’m Gonna Love You Too’. They left the double chirp on the track and henceforward were the Crickets

Released in September 1957, ‘That’ll Be The Day’ spent three weeks at number one in the American charts and sold more than a million copies, a mere hors d’oeuvre to the billions that would follow.

Norman Petty’s talents not extending to publicity, nothing was known initially about the makers of the smash hit. Groups with collective names tended to be African American and on that supposition the Crickets were booked to appear at the famous Apollo theatre in New York’s Harlem district, where few white performers and no white rock ‘n’ rollers had ever set foot.

When the curtains opened, they expected to be jeered offstage but thanks in equal measure to Holly’s showmanship and charm, were given a standing ovation.

He was to find many friends, and admirers, among African American performers, none greater than the outrageously bisexual Little Richard, with whom the Crickets appeared in a multi-act rock ‘n’ roll spectacular at New York’s Paramount theatre.

Rhythm guitarist, Niki Sullivan, later recalled their first encounter with the self-styled ‘King and Queen of Rock’ when he invited them to his dressing-room before the opening show.

The wide-eyed young Texans found Richard engaged in a complicated sex act with his stripper girlfriend and a young man he’d met earlier that day.

His international celebrity was of no avail later when he visited Holly’s fiercely segregated home city and was arrested by the police for ‘ vagrancy’ despite having $2000 in his wallet.

Holly had invited Richard home for dinner but his devoutly Christian parents shared none of his liberal values and refused to have a black person in the house. They relented when he threatened never to speak to them again if his friend was excluded.

All the Crickets were young men of strong faith but their manager/producer Norman Petty far outdid them in piety. Every recording-session was preceded by a prayer-meeting in the studio and he made each of them ‘tithe’ a percentage of their earnings to their respective churches.

Even so, Petty saw nothing wrong in claiming a songwriting credit on Holly’s original compositions as a quid pro quo for his production and technical facilities. His innocent protégé raised no objection, feeling nothing but gratitude for Petty’s belief in him and because, as his older brother Larry recalled, ‘Buddy knew he could write a new song every night.’

As an embryo rock star, he was still dating his high school sweetheart Echo McGuire, who’d kept him waiting a whole year even for a chaste first kiss. The two were eventually forced to part like a Texan Romeo and Juliet for belonging to different Baptist congregations, Echo’s so strict that it forbade dancing.

Holly was no saint; he had a long affair with an older married woman named June Clark who worked behind the cosmetics counter at a Lubbock department store, and enjoyed a brief fling with Petty’s wife, Vi, a sometime backup pianist for the Crickets.

Niki Sullivan left the group after conflicts with Jerry Allison, culminating in a fist-fight at the photo shoot for their debut album, The Chirping Crickets. The swollen eye that Sullivan gave Allison is clearly visible on the album-cover while Holly, who could think, see or hear no evil, smiles on obliviously.

In 1958, the now trio paid their only visit to Britain, accompanied by Petty and Vi. Rock tours hadn’t yet been invented; they were part of a ‘variety’ bill emceed by the comedian Des O’Connor, whom Holly presented with a guitar.

Here rock ‘n’ roll had been in disgrace since Jerry Lee Lewis’s visit the previous year when ‘the Killer’ had been revealed to be bigamously married to his 13 year-old first cousin, Myra Gale Brown. Holly, by contrast, was like a goodwill ambassador, playing music no less thrilling than Lewis’s but so pure of heart that it could be listened to, and often was, by monks in monasteries.

For ambitious learner guitarists like John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison in Liverpool, the Scotty Moore riffs and solos on Elvis Presley’s records were totally incomprehensible. But Holly’s songs were constructed from simple chords they could instantly recognise and reproduce. And the first sight of his Fender Stratocaster on black-and-white TV (which, typically, he played in a dinner-jacket) was like a blurred glimpse of the Holy Grail.

Back in New York, while calling on his music-publishers, he met a petite Puerto Rican woman four years his senior named Maria Elena Santiago. He asked her out to dinner that evening and before the meal was over had proposed to her and been accepted.

Maria Elena’s effect on the Crickets foreshadowed Yoko Ono’s on the Beatles a decade later. A tight circle of male friends felt itself invaded by an outsider, not only musically but racially. On her side, Maria Elena was presciently mistrustful of Norman Petty, in whom the guileless Holly still reposed absolute faith as ‘Papa Norman.’

By now, his hits were starting to tail off, thanks to his refusal to keep repeating the guitar-heavy style of That’ll Be The Day and experiments with double tracking and instruments like Hammond organ and celeste - all one day to become staples of soft rock.

At the end of 1958, he left Norman Petty and settled in New York with Maria Elena to be close as possible to the recording and music-publishing business. Petty’s petty revenge was persuading the other Crickets, Jerry Allison and Joe B. Mauldin, not to go with him but continue recording on their own in Clovis as if theirs were comparable talents.

He had ambitious plans to produce a gospel album and one of the Latin music he was learning from Maria Elena. He also intended to start a record label named Prism in Lubbock, with ancillary publishing and management companies and even a retailing side, much like the Beatles would attempt in the late 60s.

All this was to be funded by the royalties from his first run of hits that were still being held by Norman Petty. But Petty, that supposed fount of Christian virtue, refused to disgorge them.

So in January 1959, strapped for cash and with Maria Elena pregnant, he reluctantly agreed to co-headline a two-week tour of the Midwest billed as ‘The Winter Dance Party’ with comedy deejay J.P. Richardson, known as the Big Bopper, and 16 year-old Latino star Ritchie Valens.

He’d recently gone back into the studio in New York to try yet another new style, a set of ballads backed by a full orchestra plus strings. With what would seem horrible irony, the one chosen for release was called ‘It Doesn’t Matter Anymore’.

The Midwest in midwinter was an Arctic wilderness and the Winter Dance Party proved an ill-organised shambles with the performers continually forced to make journeys of 300 miles or more, usually through the night, in ramshackle, sometimes unheated school buses.

After the show in Clear Lake, Iowa, Holly, Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper paid $36 each to charter a light aircraft to get them to the next stop, Fargo, North Dakota, ahead of the rest of the troupe to snatch some desperately-needed sleep and send their rumpled stage-clothes to the cleaners.

The pilot of the single-engine Beechwood Bonanza, Roger Peterson, was only 21, in itself not necessarily a disqualification. But unbeknownst to his passengers Peterson was partially deaf, prone to vertigo and panic-attacks and not fully qualified for night-flying.

A few minutes after take-off, meeting a sudden snow-flurry, he lost his head and misread his instrument-panel. In the mistaken belief that he was climbing, he flew the plane nose-down at 125 mph into a field of frozen stubble and everyone on board was killed.

No one told Maria Elena, who heard the news on television the next day and was so traumatised that she suffered a miscarriage.

On tour in the U.S., Holly always carried a handgun, normality for a Texan and a necessity since he collected the payment for each night’s show in cash. When the weapon was found at the crash-site with one shot fired, a story gained traction that it had somehow gone off on the plane and caused that sickening plunge to earth.

In reality it had been picked up by a local farmer who’d reached the wreckage ahead of the emergency services and fired the shot merely to see if it still worked.

When I wrote Holly’s biography in the 1990s, I got to know Maria Elena, who’d subsequently remarried and had two children but never got over her shy, fearless first love and remained a ferocious guardian of his legacy as well as collecting the record-royalties that no one now tried to withhold.

Reaching Maria Elena required some little patience: it took me a year just to get her on the telephone and her response when I introduced myself was ‘All writers are scumbags.’

Many more effortful transatlantic calls followed before I was able to have lunch with her in Dallas and hear the whole bittersweet story of her few months with a rock ‘n’ roll legend.

From there I went on to Lubbock to see its statue of Holly with his two-horned Stratocaster and visit his modest grave bearing his true surname, Holley, and permanently strewn with flowers, plastic toy crickets and pairs of horn-rimmed glasses in case there are no ophthalmologists in Heaven.

Then I travelled the further 100 miles by road to Clovis, where Norman Petty’s studio was preserved exactly as Holly had known it. The tiny recording-space, where almost everything a pop song could say had been said between 1957 and 58, still contained his Fender Pro amplifier, at its maximum capable of just 20 watts. Nowadays when the Rolling Stones play his ‘Not Fade Away’ in some giant arena, their total wattage is around a million.

In all my travels as a music biographer, just seeing that amp is the most exciting moment I can remember.

Nice post, and will read the book, but first guitar hero? T-Bone Walker and Chuck Berry would like a word.

Thank you P.N for keeping theB.H story alive in an era which could use some True Love Ways.l.c.smith Gibsons BC